The Wyre Light was a forty-foot iron screw-pile lighthouse positioned two nautical miles offshore from Fleetwood, Lancashire, marking the navigation channel into the River Wyre. Construction commenced in 1839 under the direction of Alexander Mitchell and Son of Belfast, employing Mitchell’s pioneering screw-pile system first tested at the Maplin Sands Lighthouse in the Thames Estuary. Completed and first illuminated on 6 June 1840, the Wyre Light became the world’s first operational screw-pile lighthouse. Its success influenced later examples of the same design, including the Thomas Point Shoal Light in the United States.

Standing on the North Wharf Bank, a sandbank defining the entrance to the Lune Deep, the Wyre Light worked in conjunction with Fleetwood’s two onshore lighthouses, the Pharos and the Beach Lighthouse, to form a navigational alignment guiding ships safely into the Wyre Estuary.

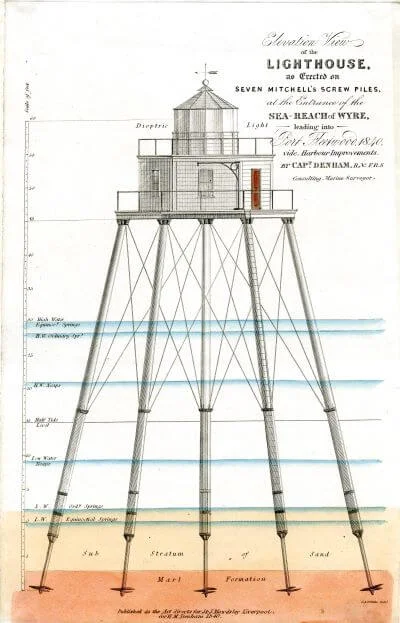

The lighthouse was supported by seven wrought-iron piles, each sixteen feet long and fitted with cast-iron screw bases three feet in diameter. Six piles formed a hexagonal platform fifty feet in diameter, with the seventh acting as a central pillar. Above this base stood a two-storey keeper’s house surmounted by a lantern, providing a prominent beacon to vessels navigating the channel.

In 1948, a fire destroyed the keeper’s quarters, leaving the structure severely damaged. The light was later automated and continued to operate until its function was replaced by a lighted buoy in 1979. For many years the derelict remains of the Wyre Light stood as a weathered sentinel off the Lancashire coast before partially collapsing into the sea on 25 July 2017. It remains a notable symbol of early maritime engineering and Fleetwood’s historic connection to seafaring and navigation.

Wyre Light Lighthouse circa 1900

Wyre Light: The Forgotten Sentinel of the Irish Sea

Off the coast of Fleetwood, on the treacherous sands of the North Wharf Bank, stand the skeletal remains of a once-pioneering structure: the Wyre Light. Erected in 1840, it was the first screw-pile lighthouse to be lit in the United Kingdom and a marvel of early Victorian engineering. Its origins lie in the vision of Sir Peter Hesketh-Fleetwood and naval officer Captain Henry Mangles Denham, who, along with architect Decimus Burton, designed a navigational system to guide ships safely through the shifting sands into the River Wyre. The system comprised two shore-based lighthouses—the Pharos (Upper) and the Beach (Lower) lights—and a third offshore beacon, the Wyre Light, situated approximately two nautical miles from land.

The Wyre Light was constructed on a hexagonal iron platform supported by seven screw piles—an innovation by blind Irish engineer Alexander Mitchell, whose design revolutionised maritime construction in soft, sandy seabeds. The lighthouse’s lantern room stood atop a two-storey living quarters, providing shelter for the keepers who were tasked with operating the light and its associated fog bell. From its first illumination on 6 June 1840, the Wyre Light served as a crucial guide for shipping, forming a transit line with the two onshore lighthouses to aid navigation.

For over a century, lighthouse keepers lived on the structure itself. These men—though largely unnamed in historical records—worked in rotation and endured long periods of isolation in harsh conditions. Life on the lighthouse was physically demanding and mentally taxing. Supplies had to be ferried out by boat, and the iron-and-wood construction provided scant protection from the elements. Despite the challenges, the lighthouse was manned continuously, and records suggest that during this period, the living quarters were functional if spartan. A glimpse into this way of life is provided by Frank Raby, a keeper who lived in a nearby shore-based cottage with his family around 1946. Although Raby did not reside in the lighthouse itself, his experience reflects the hardship endured by those maintaining it. His family endured the lack of running water, paraffin lighting, and salt-contaminated wells, echoing the difficult conditions offshore. However, this human connection to the lighthouse ended abruptly on 16 May 1948, when a training exercise involving flares went awry. A fire broke out on the veranda of the Wyre Light, quickly engulfing the wooden accommodation. The RNLI lifeboat was despatched to rescue the keepers, but the structure was beyond saving.

Following the fire, the decision was made not to rebuild the living quarters. Instead, the Wyre Light was converted into an automated beacon, operating without human presence until it was finally decommissioned and replaced by a lighted buoy in 1979. Although its navigational function had ended, the framework of the Wyre Light continued to stand as a rusting silhouette against the Irish Sea. Over time, it deteriorated further, with major structural collapse reported in July 2017. Today, the Wyre Light is a relic of maritime innovation and a haunting monument to the isolation and resilience of lighthouse keepers. No formal conservation body claims ownership, and the structure faces continued decline. Yet, it remains embedded in Fleetwood’s identity, drawing the attention of local artists, historians, and coastal walkers who remember it not just as an engineering triumph but as a symbol of dedication, human endurance, and the unforgiving nature of the sea.

Be sure to have a look at Blackpool Timeline’s posts on the other two lighthouses in Fleetwood – the Upper Lighthouse and the Lower Lighthouse.

For the Save the Wyre Light Lighthouse-Fleetwood Facebook page please click HERE.

Remains of the Wyre Light, a 40-foot tall iron screw-pile lighthouse marking the navigation channel to the town of Fleetwood. © Alamy

Fortunately, the actual searchlight was saved. You can see it at Fleetwood Museum. © Deeper Blue Marketing & Design Ltd

Image taken from the beach near the Lower Lighthouse. © Deeper Blue Marketing & Design Ltd

Close-up crop of above image. © Deeper Blue Marketing & Design Ltd

Wyre Light at Lower tide © Deeper Blue Marketing & Design Ltd

1840 elevation drawing of Wyre Light – public domain image

The derelict Wyre Light in 2007. © Antony McCann

Featured Image © Antony McCannCC BY-SA 2.0

Additional Images © Deeper Blue Marketing & Design Ltd

Background Image © Alamy